|

registration

services, made eNom the go to registrar for

many early domain investors. There is a fascinating

entrepreneurial story behind Stahura's

long and winding road to eNom and an equally

interesting one detailing his path from eNom

(after selling

the company in 2006) to his

current position at the front of the new gTLD

Army.

Stahura was born

in East Chicago, Indiana and grew up in

Hammond, a highly industrial area in

the northwest corner of the Hoosier state. The

gritty determination and untiring drive that

Stahura's friends see in him today can be

traced back to his earliest roots. Paul

told us, "My dad worked his way up from nothing

(such as no shoes) during the depression and

without a high school diploma he joined the Marines

and fought in the Pacific in World War II, got

his GED afterward and then a two-year

Industrial Management degree at Purdue

on the GI Bill. It took him 6 years to

get the 2-year degree because he did it while

working for Mobil Oil in a local oil

refinery. Eventually he became the internal

audit supervisor. It's also where he met my

mother, who was a switchboard operator at the

refinery."

|

As kids

few of us give a lot of serious

thought to what we will to do when we

grow up but Stahura experienced an unusually

early epiphany - one that would

shape his life for decades to come.

"At age 11, I saw a movie

on TV called “Tobor the Great”,

about a kid who could control a robot

from his dad’s lab basement,"

Stahura said. "I thought, “I

can make a robot in my dad’s

basement, too!” I always had

an interest in robots and things you

could control. I tried to make

one with buckets and stove pipes and

taught myself about electricity so I

could make the robot’s eyes light up

with bulbs."

"At

13 my dad got transferred to a different

oil refinery, so we moved to New

Jersey, where I went to high

school. I built two or three

more robots, which were more and more

sophisticated. In the late

1970’s I even worked at a peach

orchard for farm labor wages to earn

enough money to buy a single-board

computer—called “KIM-1”,

which had a 6502 processor. It

was the same processor used in the

first Apple computer and had 1K of

memory, which I expanded to 8K.

I still have the computer in my

library. While in high school, I read

the manual and I memorized the

op-codes and programmed it to move

the robot around my basement, and

that was my introduction to computers." |

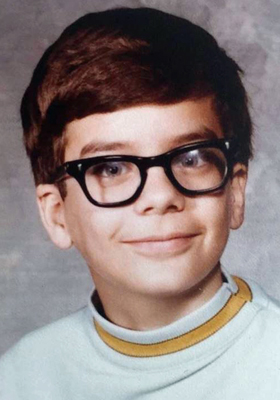

Future

roboticist Paul Stahura

in grade school.

|

|

|

Below:

The 1970s era KIM-1 computer that

Stahura

used to move robots around his

basement (he still has it).

|

"I

decided I wanted to go to college to

be a roboticist," Paul continued.

"There was a professor at Purdue

who was world famous in robotics, and

I decided I wanted to study with him.

My high school grades were not that

great but those robots I built in the

basement helped, so I was lucky enough

to get in. I did my

undergraduate work at Purdue and

eventually worked with him my senior

year. I also earned a graduate

degree in robotics at Purdue."

"After

a year and a half of grad school, I

couldn’t get robotics out of my

head. A robotics company had

moved into West Lafayette, Indiana,

where Purdue is located, and I worked

there while I finished my graduate

degree, making robotic software.

They made robots that could weld on an

assembly line."

"One

learning experience that’s stayed

with me today: Because of my bug

in the software, I once broke a

giant robot and the damage cost |

|

more than

my yearly salary, and I was sure I was

going to be fired. I wasn’t,

but it taught me you can’t make

progress without taking risks.

It’s an operating principle that I

use now with my company - you’re

never going to get fired for breaking

the robot!" Stahura smiled. |

|

|

As much

as Stahura loved robots, looking back,

he thinks he might have ridden that

horse a little longer than he should

have (a lesson he seems to be applying

today with respect to where he thinks

the future lies for TLDs). "There

are two themes to my career: Innovation

and stick-to-itiveness.

For whatever reason, once I have an

idea it takes me a long time to let

it go," Stahura allowed.

"I

met a bunch of other Purdue students

who I’m still good friends with

today, including my longtime friend Jim

Beaver who also worked at the

robot company. The robot company

eventually went out of business so I

started a robot controller company

that used the Macintosh computer—we

made control circuit boards for the

Mac and a ton of software to turn the

Mac into a robot controller,"

Stahura recalled.

"We rented some

space for our robot lab in a strip

mall next to a deli, jammed a couple

industrial robots in there, and

started writing software. A

couple of years later we hadn’t sold

one robot controller (we did sell some

related software) and we were even

more broke."

Still,

Stahura was not ready to look for another

career. "A guy I knew was building electric motors to make

modular robots in southern Indiana using Small

Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants from the

government," Stahura said. "I moved down there, and we dreamed

up a new motor, for which I got my first patent.

I was still sticking with it, wanting to invent."

|

Paul

Stahura (right) and close friend Jim

Beaver

(the best man at Paul's wedding) outside

city

hall

in Aix-en-Provence, France where

Jim is holding the

marriage certificate Stahura had just

obtained.

|

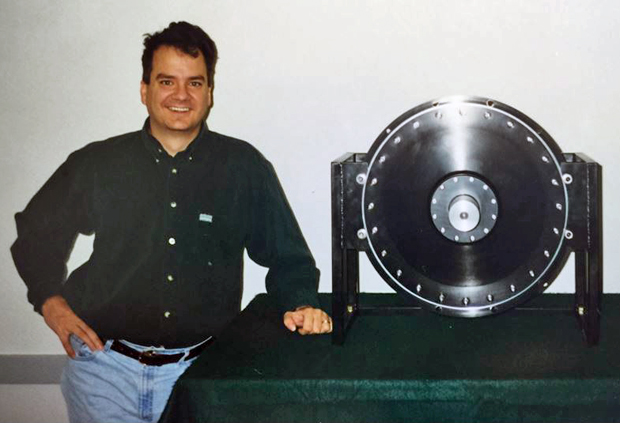

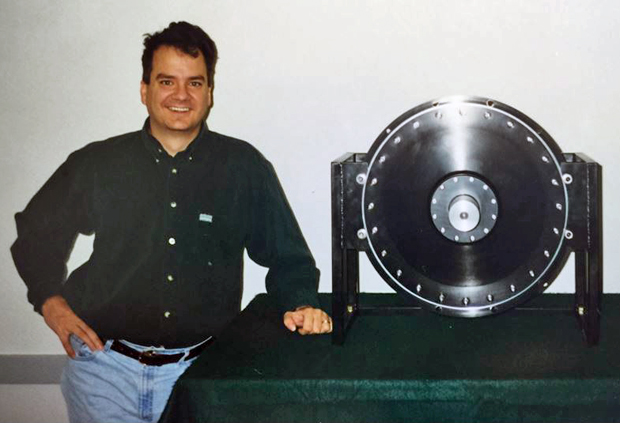

Paul

Stahura in southern Indiana with the prototype

of a

motor design he got his first patent on

in 1994.

While

Paul was deciding to stay the course in his

career pursuit, he met someone at that same

time who would change his personal life

in a very big way. "Just before I left

for southern Indiana, I met my

future wife, Flo, at Purdue where she was just

finishing her master’s degree,"

Stahura said. "In southern Indiana, I had

rented a room in a 1968

model single-wide mobile home (renting a room, because

I could not afford the whole thing), but that was an

improvement up from the farmhouse basement I was

living in initially. Flo, who is French, went

back to France to do a Ph.D. in biochemistry and so we

dated long distance for a number of years, and, I

finally asked her to marry me. She said she

would, but insisted she wouldn’t live in that

trailer. I said “deal!”, and when she got a

post-doctorate position at Notre Dame, we got an

apartment there and I was back in northern Indiana."

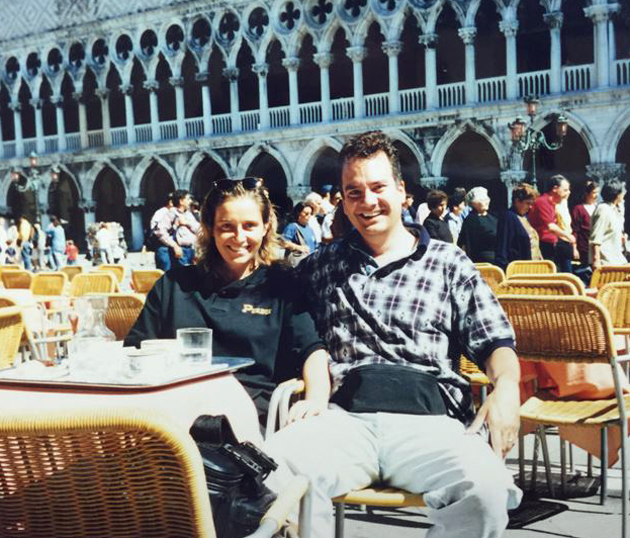

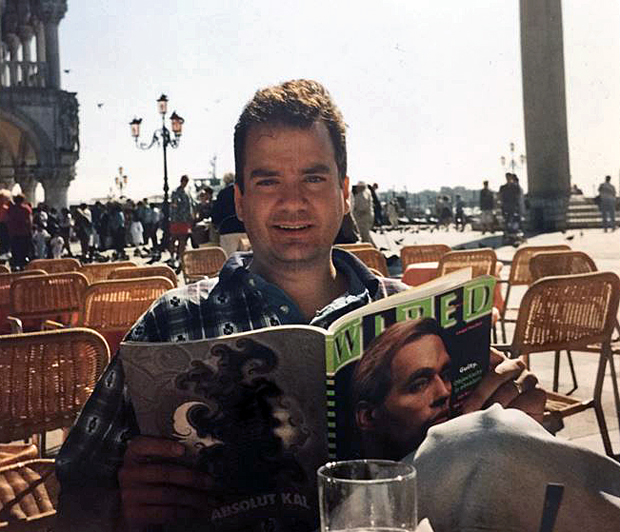

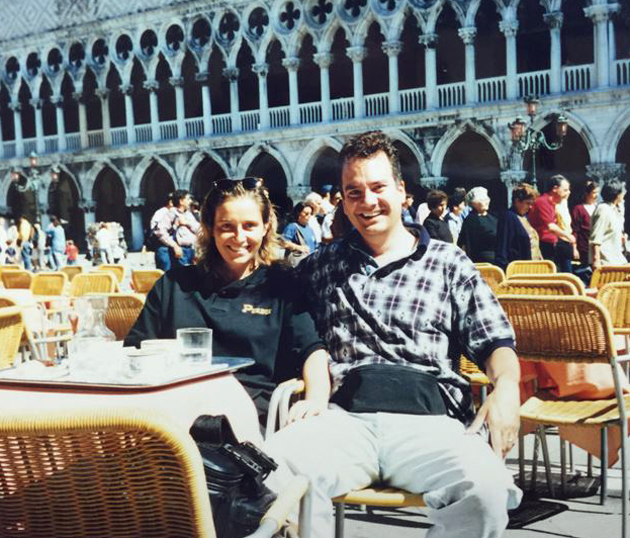

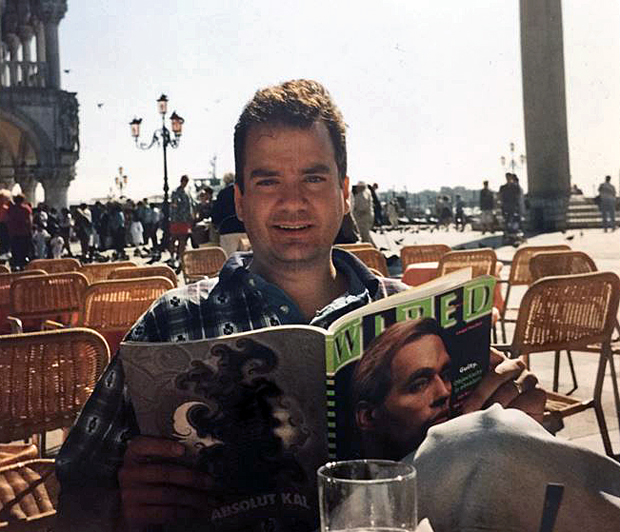

Newlyweds

Paul and Flo Stahura on their September 1995

honeymoon in Venice, Italy.

"Meanwhile, my friend Jim suggested we start a

consulting company since we knew about technology and

could continue learning new things. We started

with another three guys who knew about the consulting

business, so us “five knuckleheads” (as we called

ourselves) became partners doing client-server

consulting. I did some robotics consulting in

Michigan for a while but after about a year, I ramped

up on databases and enterprise class applications and

joined my partners in that. So after about 20

years I finally gave up the ghost on robotics and was

into client-server enterprise class applications and

sending floppy disks around to install the client

software on PCs."

"Then guess what happened?,"

Stahura continued. "The web came along,

and the newfangled universal client called “a

browser” meant we didn’t need to distribute client

software on floppies any longer. I was worried

I’d missed the revolution because I’d been stuck

in robotics for so long, but in 1995 I registered my

first domain name, Netscape had its IPO, and told my

wife I’m not missing out on this

Internet thing like I did with the PC revolution

because I was mentally stuck in the robotics backwater

due to a movie I saw when I was 11! My wife was

supportive but my partners were skeptical that the

Internet would be, as I put it, “bigger than

electricity.”

Above:

a pivotal moment in Paul Stahura's career.

"This the

exact moment I decided to not miss the

Internet," Stahura told us.

"We were on our honeymoon in Venice and I bought this

Wired magazine which was one of the only

English language magazines I could find. This article in

that issue said "IBM and Sony are reportedly planning new online offerings as well, while the existing players, ranging from

CompuServe to Delphi, are redoubling efforts to take

AOL down a peg. And the dark horse looming over everything is

the Internet itself, which some say has the potential to

doom not just AOL, but all the proprietary services, to

the ash heap of online history." I totally agreed with

that," Stahura noted. "I thought

these big incumbents (IBM and Sony) would get crushed in the new world and the Internet would dominate."

With

this belief in mind flash forward a couple of

years. Stahura said, "By around 1997 we’d built up the consulting company

to about 50 employees, but it wasn’t my kind of

business—you could make only so much money per hour

and our billable rates were maxed out, and you could

only work so many hours in a day. You couldn’t

scale and make money while you were sleeping."

"What we did have were some good developers on the

bench, waiting for work, who knew how to make great

systems. I thought we should have them work on

provisioning a service we didn’t have to ship,

something that had to do with the web. All these

folks in the popular technology press were talking

about web browser war this and web server that, but I

saw that there these things called name servers, which

a bunch of geeks could set up and was something your

website needed to work. It just seemed like name

server tech had more opportunity per person working on

it than web server tech had. The DNS was central

to how the Internet worked, and I told my partners we

should get into name server services because there was

too much competition doing web stuff," Stahura

said.

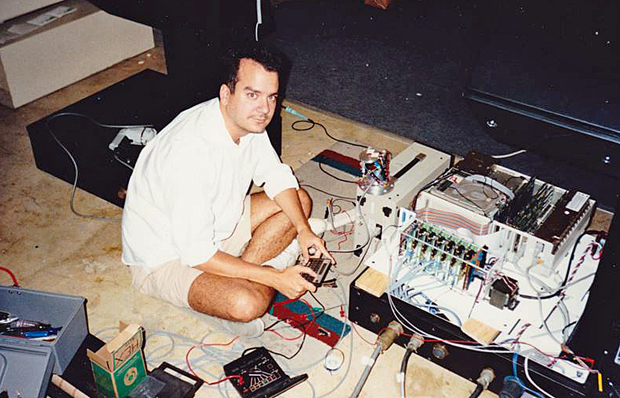

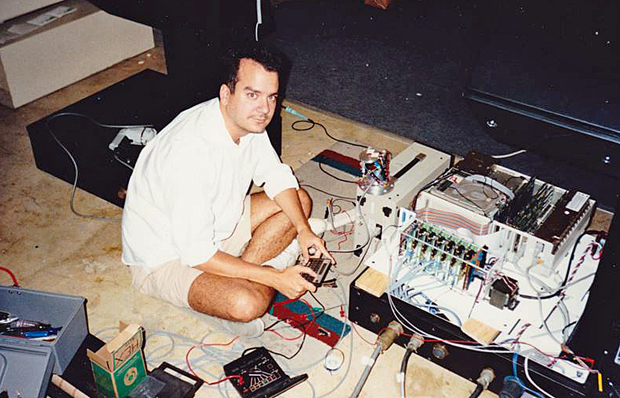

In

1992 (when this shot was taken) Stahura was

still all about the hardware.

Little did he know that five years

later his focus would switch to software

(For

historic hardware fans Paul is working on a robot controller made out of a

Macintosh II. Stahura noted, "You can also see my handy dandy HP 11-C (I still use that same

one - its on my desk now!) and you can see the cool/innovative 6-degree-of-freedom

“stewart platform" joystick just to my left

which we used to control/move the robot with (I still have it too).

its funny to see a drill, a tool box, a soldering iron and the volt meter in the picture, when nowadays we are so far removed from hardware and mechanical things."

Returning

to the late 90s, Stahura said, "A couple of guys had set up a web-based interface to a

mail server and called it “Hotmail” and after just

18 months sold it to Microsoft so I suggested we

make a

web-based interface to a name server. Before

that, there was no remote access—you had to call a

geek at an ISP or somewhere who was sitting in front

of the name server to type in magical stuff to get

your name to work and point to your web server’s IP

address. I figured we could charge people for a

simple “do-it-yourself” web interface that made

names work for them (everyone got the actual names at

NSI back then, because that was the only place to get

names, but NSI didn't offer DNS)."

"We made the software and in thinking of a name for the

service, we came up with eNom. eName.com was

already taken, and so was Name.com. I had my

wife translate “name” into French, which is

“nom.” I stuck an “e” in front like

“eBay”, and I also liked the four-letter name and

thought if it became big, it could be a stock symbol

on NASDAQ. eNom now owns name.com and is a

public company on NASDAQ as part of Rightside, but

trades under the symbol “NAME”, not “ENOM,”

Paul noted.

(December

5, 2014) The Rightside team at the NASDAQ

Exchange in New York City

on the day the company's stock started trading

under the NAME symbol.

In

eNom, Stahura was finally able to realize his

dream of creating a scalable business that

would make money while he was sleeping.

Even though it proved to be a great idea,

Stahura still had a hard time getting his

partners on board. "We got into the domain name

system. I pitched my

partners with “it’ll be a bank machine on the

web,

but people will put money in instead of taking money

out, and we don't have to ship anything, just make an

entry in a database”. But that didn't get me very

far, and my partners didn’t really go for it—they

wanted to be in the consulting business, “this is

the business we have chosen,” they’d say, quoting

a line from the Godfather movie. I finally

convinced them by saying I would do it myself, so I

put up 1/3 of the money, and they put in 2/3—

the

consulting company owned the majority of eNom."

"In 1997,

CORE had started and announced that TLD

contracts were running out at Network Solutions, then

the only registry and registrar. They wanted to

create seven new TLDs, and said if you show up at a

meeting in Tokyo with $10,000, you could be a member

of CORE and participate in getting these new TLDs

launched. I scraped up the money and flew over,

and met half the people in the industry at the time (Hal

Lubsen, John Kane, Ken Stubbs, Amadeu Abril de

Abril, and many others). This is how I got into

domain names."

"So

1997 is when I got hooked by “.web” – my second

passion after robots – a domain name registry.

I tried to get into TLDs with CORE then but incumbents

made it so that it didn’t happen. What did

happen was the TLD idea lodged in my head.

ICANN

then began in 1998, and split the industry into

registrars and registries. eNom became

accredited as a registrar, but we weren’t among the

five companies in the original registrar “test

bed”. I had investors lined up to back eNom if

it had been in the test bed, but they all backed out

when they learned we weren’t. We were all on a

conference call where ICANN announced the test bed

participants, and when eNom was not announced, my

potential investors literally got up and walked

out," Stahura recalled.

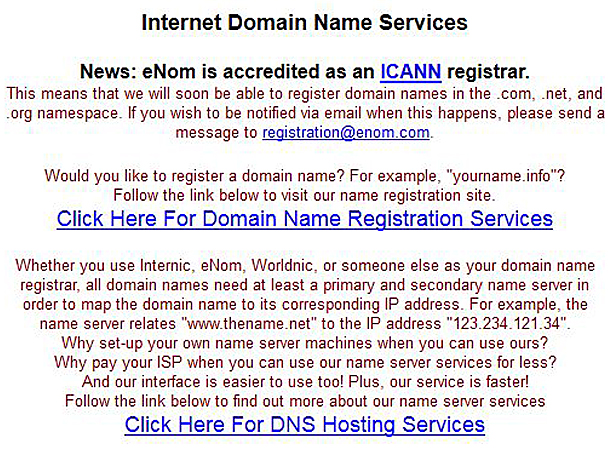

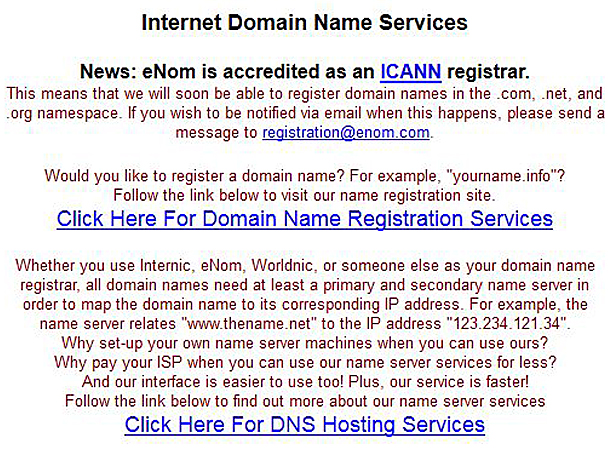

Below:

A screenshot of the eNom Home Page in 1999

from the Internet

Archive Wayback Machine

Stahura

still found a silver lining in the test bed disappointment.

"The

good news is that eNom, because it came out of the

consulting business, was over-architected (in a good

way) with a “tiered” architecture," he noted.

"We

registered our first name, which was

“competitionworks.com” (because it does) using the

API in 1999 (the whois recorded the exact day and

time) and we decided we would open our API to anyone

to use, and this became the basis of our reseller

model. Our motto was “We Suck Less” (than NSI, the

near-monopoly back then). We were provisioning name

server services, and said, “let’s provision domain

names too.” Eventually we provisioned e-mail,

an ID protection product for WhoIs (something John Kane –

who later joined me at eNom and is now at Afilias —

and I dreamed up in the late 1990s) and other

services. We just kept adding to it,"

Stahura said.

"So

I had successfully transitioned from robotics, via

consulting, to the Internet. It felt as though

I’d emigrated from the U.S. into cyberspace—I was

living in another world called the Internet."

There

is one bit of eNom history that only long time

industry observers may recall. We noted earlier

that Stahura sold the company (to Demand Media) in

2006, but he had actually sold it once before and had

to take on a major risk to get it back. Stahura

explained how that happened. "From 1997 to 2000, we built both the consulting

company and eNom. In 2000, we were approached to

buy the consulting company. In due diligence, it

was learned the consulting company owned most of eNom

and the acquiring company, Webvision, wanted to buy

eNom too, so we sold both. Within about a year

Webvision blew through all the capital it had raised

and went out of business. Just before its final

collapse Webvision ran a process to sell eNom, which

included new.net (an Idea Lab company back then) as

one of the bidders. Jim and I scraped together all the

money we had, taking out second mortgages, and ended

up with the winning bid in buying back eNom."

|

Legendary

domain investor and

Uniregistry founder Frank

Schilling

helped eNom discover "the

drop". |

"After being cocooned within Webvision during most of

the .com bust, the eNom butterfly emerged between 2002

and 2006," Stahura said. "We had great architecture that worked

and was scalable and didn’t fail very often—we had

an API and were hosting other ICANN registrars,

performing “back-end” registrar services for them

as well as ourselves and all of our customers."

"At one point, we noticed at a certain time of day our

systems were pounded. Why was Frank Schilling

pounding our servers every day? We found out

this was due to the “drop.” We got wise to

the drop and the idea of “creds” (a term we

invented to mean the login credentials to an ICANN

accredited registrar). We applied to ICANN for

hundreds of “creds” to have many more bites at the

registry SRS apple and founded Club Drop (which

eventually became NameJet in 2006). We got into

parking and we started competing with SnapNames and

Pool.com," Stauhura noted

"Through many twists and turns and ups and downs, we

grew from our API, resellers, the drop, parking, and

value-added services. Providing real value at

low prices made eNom |

|

thrive. This whole time,

however, I hadn’t given up on the idea of new

TLDs.

I tried often to get control of a TLD between 1997 and

the opening of the current round - .WEB, .ID, .MY,

.CO, .ME, .ONE, .ORG - I was unsuccessful at least

seven times. Before 2014 I was the biggest TLD

loser ever. Still, I stuck to it because I saw

the need for an expanded name space. As the

years went by, the quality of new names in old TLDs

got worse and worse and the pushback from incumbents

to new TLD competition got greater and greater."

|

|

|

Before

Stahura would get to the new gTLD

destination he hoped to reach his baby,

eNom, would be sold a second time.

"

In 2006 investors of Demand Media approached us to buy

all of eNom, not just because of the registration

business but because of the portfolio and parking

revenue we’d built," Stahura said. |

|

|

"Their model was that of a

media company that monetizes content through ads; we

were getting huge revenue from parking, which is

nothing but monetizing ads but with no content.

At first blush it would seem like a domain name

registrar has nothing to do with a media company, but

it was as if they intended to publish magazines

(websites with content and ads), while we published

catalogs (our domain name parking, which is nothing

but ads). The synergy came from the fantastic ad

rev-share eNom had back then with Google and Yahoo." |

"We formed Demand Media and that same day in 2006 sold

eNom to it, and I was President and COO of Demand, and

as a large shareholder also a member of the board of

directors. The company acquired more and more

media properties and some other registrars. But

I still had my heart set on climbing that last

mountain—getting a new TLD. I spent a lot of

time at Demand working the policy process of advancing

new TLDs. After yet another delay in the TLD

program, which made it look as though new TLDs were a

long way out, I left Demand Media in late 2009."

|

|

Less

than two years later Stahura was back

in the spotlight again - this time

in a role he had been seeking for nearly

two decades - running a company that

operates its own gTLDs - and not

just any company - one that has

become the largest in the space - Donuts

Inc. To get where he wanted

to go Stahura spent the time after he

left Demand Media putting together a top

tier group of co-founders and raising a

9-figure war chest to fund the

ambitious venture.

"I had known my Donuts

partners for a long time from our years in the

industry," Stahura said. " At first,

Richard Tindal (Chief Operating Officer) and I were partners,

as were Jon Nevett (Executive Vice President,

Corporate Affairs) and Dan Schindler

(Executive Vice President, Business

Development) separately, but eventually we

decided to all go in together. Jon was Sr. VP at

NSI, Richard ran Neustar’s registry business (he

obtained and ran .biz and .us for them) and Dan ran

CentralNic They are all tremendous

professionals, very talented, and we compliment each

other well.

|

|

I couldn’t ask for a better team of

co-founders and its great to work with close friends

at Donuts just like it was at eNom."

Donuts

Co-Founders (left to right): Paul

Stahura,

Dan Schindler, Richard Tindal

and Jon Nevett. |

"Due to the mutual respect all of us at Donuts have for

one another, we are not afraid of conflict among the

team because we know we’ll use reason and logic to

get to the right answers and make the best decisions.

Tren Griffin quoted Ben Horowitz who quoted

Marc

Andreessen who quoted Lenin who was quoting

Karl Marx

who said “sharpen the contradictions”. We,

too, believe that works. Nothing is perfect.

Surfacing the differences and reasoning them out,

getting to the truth, and resolving them is best, not

plastering over and hiding conflicts," Stahura

said.

The founders all have great credentials but

raising hundreds of millions of dollars is still

an impressive feat. To get it done, Stahura did

something he had done before to get eNom off the

ground. "The first element of raising

the capital was that I put up my own money as a

testament of my faith in the opportunity,"

Stahura said. "I

figured it's a risk only if you don't know what you

are doing, and I was pretty sure we knew what we were

doing. The second was that we had a very

believable reason why we could acquire TLDs in an

economical way, and further, why other companies

wouldn’t make as big a play as we were proposing.

As Warren Buffett says, “if its raining gold, put

out a bucket”, and I figured they’d put out a thimble. Once I invested,

TL Ventures and Austin

Ventures joined, and the other investors came along

seemingly fairly easily."

"Donuts

is the first company for which I raised money – eNom

had no outside investors before I sold it to Demand

Media but I had learned a lot from the management team

at Demand Media, which had the motto “go big or go

home,” and raised over $200 million. I wanted

many

new TLDs, and obtaining many new TLDs is a capital

intensive venture, so I had to assemble a great team

and raise a lot for Donuts. I had the wherewithal to

lead the way and that started the ball rolling, and

also large venture capital and private equity funds

need to deploy capital in big chunks (but only to

entrepreneurs with valid, believable reasons why a

large amount is needed and how they’ll certainly

make money for their investors). It’s probably

harder to raise a small amount of capital with the

same amount of good reasoning," Stahura opined.

|

"Like eNom and the

drop, we decided to go big— this time, instead of

300 registrar creds, it was 300 new TLDs. I am

fortunate to have been joined by world-class investors

who have never been anything but supportive of the

Donuts management team and excited by new TLDs, domain

names, and the registry business. Again, it’s

great sailing with friends who are all highly

motivated to get the ship to port."

"From back when I was a kid, I was stuck for 20 years

on robots, but for the last 20, I’ve been stuck on

TLDs. I’m involved with Donuts now because I

couldn’t get TLDs before, when I initially wanted

to. Finally, ICANN is overcoming the incumbents

and opened the window and after all that time we got

our first new TLD last year. I don’t give

up—in fact, I’d have to be dead before I give up.

I stick to things because I fixate on them and

innovate ways to make them come true,"

Stahura said.

|

|

Donuts recently celebrated the 1st anniversary of

its first TLDs going live. We asked Paul how, at this

early stage, his strategy has played out

compared to the vision he had for the company going

in. "It’s going almost exactly as we thought it would,

but for one thing," Stahura said. "For example, we thought

we’d have 150 uncontested TLDs; it turned out to be

149. We thought we’d end up with about 200

TLDs in total, and that’s just about the number

we’ll end up with. The exception is that it happened

nowhere near as fast

as we thought it would. The process took much

longer than it should have. It took too long to

get these assets in the hands of the public, open the

name-space, bring innovation, and create real

competition and lower prices. But I believe in

Warren Buffett’s maxim that it’s better to have

the “what will happen” right versus the “when it

will happen," Stahura said.

Despite

the seemingly endless delays, Stahura said one

thing remained the same - a determination to innovate.

"We

innovated pricing tiers at Donuts—this wasn’t

easy, as we had to do that while staying compatible

with standard EPP so registrar integration would be

easy. Now other registries are doing it.

We innovated the Early Access Program (EAP), and now

other registries are doing that. We innovated

the Domains Protected Marks List (DPML), and

registries are doing that as well. We innovated

private auctions to resolve contention among TLD

applicants, which was initially rejected but is now

wholly embraced. We have a few patents in the

pipe, and we’re innovating other things we have yet

to launch. The Donuts DNA is infused with

“Innovation is the key to wealth creation”,

Stahura said.

|

|

Paul noted,

"Even

our name is creative. “Donuts” evokes

variety and choice because bakers create so many

different types of donuts. We are nuts about

domains (“domain nuts”). Its memorable because

it's a bit strange. You’ll notice that our

name contains the letters “DNS” which are

highlighted in a |

|

different color (similar to

“Hotmail” containing the letters “HTML”). And

have you noticed the first letter, “D” is the

color teal?—a “teal D”. Aren’t we funny?,"

Stahura smiled. |

While

Stahura is confident that big things are

ahead for new gTLDs, others, especially those in

the domain investor camp, think it's unlikely

new extensions will ever be able to escape .com's

long shadow. Stahura explained why he thinks his

vision of the future is the one that will play out. "New York City was big in the

1700s and is big now—it

will be the biggest city in America probably

forever," Stahura noted. "However, and this is

important, its population is

becoming less and less of the total population pie.

Las Vegas, San Francisco, LA and

Chicago didn’t

exist when New York was founded, but they’re

significant today and are now thriving cities.

The same is true of TLDs. All these new cities

had great new real estate for various reasons – next

to the lake, on a river, near a port, on a hilltop —

just as new TLDs do."

"We’re still at the

very beginning. There will be no

other globally unique naming system – the DNS is too

embedded into our Internet, our laws, our

communications, and our world. The Internet will be

around for more than 100 years (like the phone system

has been), and these names will be too. New

domainers and some old timers recognize this new

opportunity and are moving west. Some old timers

are mentally stuck back on Plymouth Rock. Some

slumlord probably said back then “Don't go west

young man, there be lawless savages out there!

Rent my tenement in Brooklyn instead,”

Stahura said.

|

"Our

“cities” are new and sit on great real estate,

vast swaths of which are still unexploited,"

Stahura continued. " A

new name in .COM is probably in a bad neighborhood and

is not next to Central Park in New York—there’s no

good land left there. There’s good new

unregistered land in new TLDs, and they will be around

for a very long time. For sure, a condo on Park

Avenue is worth millions today, and if you are lucky

to have bought it back in 1960, congratulations, you

probably beat inflation, but buying it now |

|

|

will cost a

buyer millions. Potential investors have to ask

themselves: “Will the condo value go up faster

compared to buying some undiscovered great properties

in a brand new city now, and for less?”

|

"But its not just some domainers leading the way to new

TLDs," Stahura noted. "Brands are moving west too. Domainers are

accompanied by trend setters such as Lady Gaga with

bornthisway.foundation, Lionsgate with

thehungergames.movie, Kanye West with

yeezy.supply, GM

with GeneralMotors.green, McDonalds with

bigmac.rocks,

and many others now and many more to come. It's

not a coincidence that companies like Google and

Amazon got into both the domain name registry and

registrar game right when new TLDs were launched.

I’m sure its not because they think it wouldn’t

last or be huge."

Stahura

added, "The

NSI registrar had about 100% worldwide market share

when I started eNom in my garage on near zero capital.

Look what happened. The Verisign registry had

about 50% worldwide market share when I started Donuts

with over $100 million in capital. We’ll see

what’ll happen."

|

|

While

we all wait to see what is going to

happen it's hard not to marvel at how

one man's life can change in the space

of 20 years. Reflecting on that Stahura

mentioned, "

I’m married with three teenagers now. I didn’t

have teens when I started eNom in my garage. Our

oldest was just born and we had a sign on the door

asking people not to slam it and wake up my daughter

when they went inside to use the bathroom!,"

Stahura laughed.

Paul's

business and personal life were

intertwined back then and that is one

thing that hasn't changed. "I

like working with people I like, so I don’t separate

friends from business that much," Stahura

said. " I like going to

ICANN meetings because I have a lot of friends there.

I don’t have a hobby outside of work—it’s not

really work to me. There’s very little

“outside of work” for me."

"I

travel with my family but my mind is often on business

and domain names because I’m fixated with it.

Flo has gotten used to it, I think. We are just

back from the Galapagos, where my family and I

explored the wildlife and jungles, and after the

Durban ICANN meeting my family and I did a safari in

Botswana and other countries there. We travel a

lot and go back to

|

|

France to visit my wife’s family

there. Despite my fixation on the DNS, I think I

have a healthy work-life balance now and at times in

the past, but it has not always been easy to

achieve," Stahura said, clearly very

content with where that 11-year-old

kid who loved robots is sitting today. |

|