|

|

Emily

Hale

The Water School |

For

the full and far more interesting answer, we

turned to Water School representative Emily

Hale who was on the climb team and kept a

detailed journal of the assault on the summit and

the subsequent descent - both of which took a

heavy toll on the intrepid climbers. From this

point forward, I will let Emily's report tell the

story in her own words.

Emily

Hale: For the climbers, the six-day

trek was one of the greatest accomplishments

they have ever achieved. On Day One

(Monday, March 1) all climbers made their way via

van and bus ride up the steep road to the gates at

the foot of the mountain. We were graciously

welcomed to the mountain by our leader Godfrey

and assistant guide Robert. These two

individuals would lead the way through fog, rain,

hail and ice for the following six days! |

Accompanying

our group were 64 porters to carry tents, food and

luggage up the mountain for the climbers. We all

discovered very quickly that these porters had more

strength and perseverance than all of us combined! Just

five minutes into the walk the African skies opened and

the rain poured down. Seven hours later and about

18 kilometers down the path, we arrived at the Machame

camp site (2,890 meters high), wet and tired.

|

The

porters set up camp, with over a dozen sleeping tents, dinner tents and cooking tents. The problem was locating your designated duffel bag of clothes and supplies among the mounds of other bags. Sure enough, one duffel bag, which was shared by two of the

climbers, Tessa Holcomb and Kamila

Sekiewicz, (both from Sedo.com) had been misplaced and

left at the hotel! The two women were quickly outfitted in borrowed clothes and sleeping bags, and arrangements were made to receive their duffel bag the following day. The best part of day one came around

7pm when we were presented with a hot meal of delicious soup and vegetables. We all left

dinner exhausted and longing for |

On

Day One, Tessa Holcomb and Kamila

Sekiewicz

reached camp but their duffel bag didn't! |

| bed.

The drop in temperature was surprising, as it

dipped below freezing. This made sleeping

very difficult for those who were novices at

camping in the cold. |

Day

two began with a hot breakfast of cream of wheat, eggs, and sausages. The climbers prepared for the day’s hike, filling day packs with

water bottles, protein bars and rain gear.

As the climb resumed, people began to separate into

groups - the individuals who preferred a faster pace lead the way, while those pacing themselves formed their own groups behind. The rainforest disappeared and

shrubs and moss like bushes covered the ground. Half way through the day everyone met for a hot lunch, which had been set up in the middle of an open

area with two large tents. The climb continued after lunch, but the sunny skies were soon replaced by dark clouds and the

rain began to pour again. Fortunately, it was a shorter day, only 9 kilometers of hiking until

Shira camp at 3,840 meters high. After dinner, fatigue set in and everyone was off to bed after their pulse and oxygen levels had been checked.

Temperatures were again well below freezing. The

day three climb was extremely rocky and climbers learned the importance of carefully placing your steps to avoid slipping or rolling an ankle.

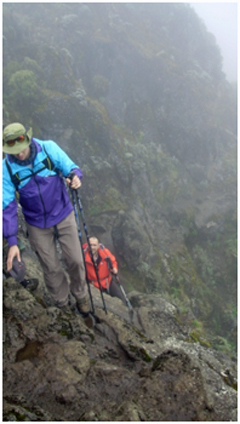

Climbers

navigate through a rock-strewn path on day three. The 15 kilometer

leg on day three was separated by lunch at the highest point, known as

Lava Tower, at over 4,600 meters high. We then

wound around to Barranco camp which we reached by

early evening. This camp was situated in a valley, and oddly enough, climbers were able to find reception for their cell phones if they were standing in just the right position, facing just the right direction, at just the right angle. By day three, some people were showing signs of

altitude mountain sickness (AMS), and suffered headaches and nausea. A hot supper was well received and worn out climbers quickly situated themselves inside their tents and slept in the frosty temperatures which surrounded them.

|

Day four would turn out to be a

very long and cold day for some. It would also be the

last day before the most important event of the climb –

the summit! The first part of the morning was the most challenging. Climbers would test their skills and agility climbing almost

straight up what is known as “the Barranco

wall”. Every step had to be carefully placed and weighted against the

rocks. Looking down would only make matters worse, since the valley was steep and the bottom appeared many meters away. The second half of the trek continued after lunch, but seemed

never ending. The trails were winding and steep as they wrapped around the mountain side, going up and down at steep inclines. The 15 kilometer

day four hike took everyone well into the late afternoon to complete. The worst weather conditions

also came on day four. As the temperatures dropped, the rain that everyone had been used to

transformed into ice pellets which violently cascaded down from the sky. Arriving to

Barafu camp by early evening, the tents were

covered in ice. By the time everyone arrived it was dark and

climbers were reminded that they should get as much rest as possible before attempting to summit in the early hours of

day five. |

Matthias

Kaiser & Uzay Kadak

make their way up the Barranco Wall

on day four of the Kilimanjaro climb. |

Being woken in the

first hour of day five was shocking to most. The climbers arose from their tents distraught and exhausted from the long day of hiking on day four. Godfrey had informed everyone that the summit attempt would be

long and dark. The standard attempt would take about

eight hours to reach the summit, Uhuru Peak

(5,895 meters), and then the descent would take another few hours. There wasn’t much time for breakfast,

so instead climbers filled their day packs with protein bars, energy gels and water bottles. Equipped with only day packs and head lamps, at

2am climbers began making their way to the summit. Almost immediately the group was separated by pace and two smaller groups formed, each with a guide and a few porters which would stay nearby in case anyone needed assistance.

Nausea, vomiting, headaches and exhaustion were all common symptoms of high altitude. At this point one of the climbers faced

severe AMS and was forced to turn around and return to camp.

|

|

Sunrise

over Muru peak |

Slowly the groups made their way up the snowy peak. Zig zagging across the rocks to make it easier on the body, the scene could be compared to watching a movie in slow motion. The

lack of oxygen prevents any kind of speed or exertion in a person’s step. Taking breaks every hundred meters is essential in order to catch one’s breath and regroup from the nausea and headaches. The sunrise over

Muru peak in the distance was breath taking

and stopped everyone in their tracks for a few minutes. The sunrise meant warmer temperatures were on their way and the heat would help to thaw frozen fingers and toes. |

Conquering the summit took

pure willpower and determination for everyone. Sure enough, by the time the sun was beaming down on the mountain, the first group of climbers could see the top. However, the group quickly realized that although the top was in sight, the peak, called

“Stella’s Point,” would take another hour of climbing.

The snowy trek to the peak was even more draining due to the lower oxygen levels.

|

At last, the first team of three,

Todd Erhlich, Mick Honan and Emily Hale reached the peak in an astonishing time of five-and-a-half hours!

Victory!

This would be just the beginning as the other 23 climbers made the summit in the following hours of the day, and into the afternoon, scattered into groups of two or three. The only thing which kept most people going was the enthusiasm and encouragement from fellow climbers who had just visited the peak and were making their way back down the mountain.

The sign on the peak explained it all, congratulating us for reaching the

highest point in Africa at 5,895 meters high! Customary pictures

with this sign were taken as proof that a climber

had reached the summit. After |

Jazmin

Carillo (Parked.com) - one of the 26

climbers

who reached the summit of Mount

Kilimanjaro. |

| photos

and many hugs with those who had joined the

journey to the top, climbers slowly made their way

back down. It wasn’t possible to spend much time

enjoying your triumph at the peak due to the thin

air which caused dizziness and

disorientation. |

|

Climbers

making their way

back down from the summit. |

The

climb back down seemed almost as difficult

and much longer. The daylight hours made the

mountain appear like an endless path winding down,

and the camp would not be in sight until the last

few hundred meters. On the way down from the summit

we all realized why climbingin the dark was vital to successfully completing the climb: the darkness hid the daunting height of the mountain forcing climbers to focus only on the steps in front of them.

Those who had first descended from the summit had time to rest and pack their belongings to move camp down the mountain to a site called

“Millennium”. The groups were still |

| scattered,

and it wasn’t until part way through dinner that

everyone arrived. The final night on the mountain

was quiet and everyone was anxious to begin the

final descent the next day and reward themselves

with showers and restaurant food! |

|

For almost everyone,

day six (Saturday, March 6) had started out like any other; packing and breakfast followed by getting ready for the day’s trek. Unfortunately for one individual,

Gregg |

| McNair, his feet had been so badly damaged

by the previous day's descent from the mountain that he called for help. The option of getting a helicopter was quickly diminished as the price increased more than ten-fold in a matter of hours! The only other option was a

wheel barrow like stretcher that he would be affixed to by ropes.

With Gregg tied to the stretcher, porters quickly pushed

it down the mountain, jolting and dislodging Gregg

to the point |

This

"stretcher" carried an injured Gregg

McNair

the balance of the way back down the mountain. |

| that

the stretcher almost flipped over several times.

Near the base of the mountain a jeep was able to

pick Gregg up, along with a couple others, and drop

them off at their final destination, Mweka

gate. By this time, most climbers were waiting and

the porters and guides said their final farewell

with a feast they presented to us. |

|

|

A

feast and farewell speeches

awaited the climbers after their

successful conquest of Kilimanjaro |

Speeches were made on behalf of

The Water School, congratulating everyone for their success and sponsorships of almost

$200,000 donated towards the Climb for Clean

Water.

By early afternoon, everyone headed back to a local hotel in

Moshi. Showers began running, drinks began pouring and

a long night of celebrating had just begun! Although the climb had physically ended, the event marked the start of many great things to come for

The Water School, and most importantly, thanks to

your contribution to the climb, over 20,000

people will have clean water for life!

One of the best

parts is knowing that 100% of your donation

is actually being donated, this is thanks to a

generous donor who has covered all administration

costs for 2010! That means each and every cent

is going directly towards implementing the Water

School Program, which is proven to protect children

and families from death due to consumption of

contaminated water.

Thanks again for making the climb a

great success! |

|

| And we

thank Emily for that fabulous first person account

of the group's adventure. And by the way, who said

it is "A Man's World"? The ladies

of Kili 2010 take a back seat to no one!

Though the climb is

over it is not too late to make

a donation to The Water School. The only

reason all of those climbers put their bodies on

the line is because they knew how much good every

single dollar contributed to the cause would do.

We congratulate each one of them for their great

accomplishment and effort to help less fortunate

people in developing nations overcome disease

and death that have been spread by waterborne

illnesses that the The Water School is working to

eradicate. |

The

Ladies of Kili 2010 |

Sedo's

Kamila Sekiewicz and Tessa Holcomb with

some

of the young students at The Water School in Tanzania.

|